Contents | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 En español

Puerto Peñasco

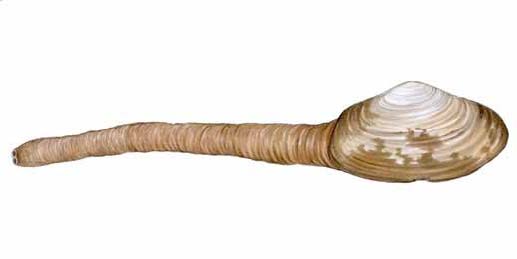

The Chiluda Clam

Clam opens something new for fishermen

For many years, the people of Puerto Peñasco have distinguished themselves in the fishing export business. They endure both the ups and downs of the fishing seasons and the fluctuations in the global economy. Currently they negotiate threats presented by the sharp contrast between the increasingly intense demand and the increasingly limited supply of seafood products. In this context, the hopes of some cooperatives lie in the harvest, processing and future sales increases of a curious and coveted mollusk, before unknown in this area. We refer to Panopea globosa, known as the “almeja generosa” or “chiluda” clam in Spanish and the Cortez Geoduck in English. This mollusk has gained familiarity thanks to Lázaro “Chichi” Espinoza, a fishermen from the Mar y Tierra del Golfo de Cortés fishing cooperative, who, on a trip to Ensenada, Baja California, watched with awe as the strange looking clam was extracted from the nearby waters. He was certainly able to appreciate its high market value, up to $8 per clam. He set out to discover if the clam could also be found in Puerto Peñasco. He sent out divers every day to look for the clam. At first, the search was unproductive. But on one of those many days, they finally found a Cortez Geoduck. They took it to CEDO (Intercultural Center for the Study of Deserts and Oceans) so that they could carry out research into the species. The cooperative hoped to be able to initially obtain an investigative fishing permit, that would lead to the future sustainable commercial harvest of the clam.

Now, the Mar y Tierra del Golfo de Cortés cooperative has become a pioneer, being just one step from achieving their goal of qualifying their activity as sustainable. In this manner they hope to increase both the alternatives for consumers as well as the opportunities for their families. At the same time they hope to reduce the pressure on other species that are scarce and to strengthen the local economy.

For many years, the people of Puerto Peñasco have distinguished themselves in the fishing export business. They endure both the ups and downs of the fishing seasons and the fluctuations in the global economy. Currently they negotiate threats presented by the sharp contrast between the increasingly intense demand and the increasingly limited supply of seafood products. In this context, the hopes of some cooperatives lie in the harvest, processing and future sales increases of a curious and coveted mollusk, before unknown in this area. We refer to Panopea globosa, known as the “almeja generosa” or “chiluda” clam in Spanish and the Cortez Geoduck in English. This mollusk has gained familiarity thanks to Lázaro “Chichi” Espinoza, a fishermen from the Mar y Tierra del Golfo de Cortés fishing cooperative, who, on a trip to Ensenada, Baja California, watched with awe as the strange looking clam was extracted from the nearby waters. He was certainly able to appreciate its high market value, up to $8 per clam. He set out to discover if the clam could also be found in Puerto Peñasco. He sent out divers every day to look for the clam. At first, the search was unproductive. But on one of those many days, they finally found a Cortez Geoduck. They took it to CEDO (Intercultural Center for the Study of Deserts and Oceans) so that they could carry out research into the species. The cooperative hoped to be able to initially obtain an investigative fishing permit, that would lead to the future sustainable commercial harvest of the clam.

Now, the Mar y Tierra del Golfo de Cortés cooperative has become a pioneer, being just one step from achieving their goal of qualifying their activity as sustainable. In this manner they hope to increase both the alternatives for consumers as well as the opportunities for their families. At the same time they hope to reduce the pressure on other species that are scarce and to strengthen the local economy.

Life-giving Clam

The Sea of Cortez has many known types of clam. Among these, the chiluda is the largest and the longest growing in the world. It reaches maturity after four years, at which age it is able to release eggs and sperm into the water. The two will unite to form “seeds” (larvae) that travel on the marine currents over a 48 hour period. After that, their shells begin to grow and they will attach themselves to rocks, algae or corals. Soon thereafter, they will bury themselves in the sand where they will grow to reach maturity and release their own eggs and sperm. In Mexico’s northwest, other than reproducing near Ensenada, the Cortez Geoduck also can be found in San Felipe, Baja California. The difference with specimens found around Puerto Peñasco is that they reach a larger size at a younger age than do those found on the other side of the Sea of Cortez.

Divers carefully extract and process clams

The extraction method for this species is just as strange as the mollusk itself. The divers harvest the clam during is a dead tide, when the sea is at its calmest and they can do their best work. They use a pump with two hoses; one of these sucks out sea water and the other shoots it directly onto the area where the clams are buried. Using this siphoning process the divers make circular rings around the location of the clam, carefully unburying it without causing it any damage.

Currently there are three cooperatives involved in the harvest of the chiluda. They use all nine of their launches to transport the clams to the recently constructed processing plant at the Mar y Tierra del Golfo de Cortés cooperative. The cooperative rents space to the other two, the Sonora Cooperative and The Jaiberos y Escameros Cooperative. Each of the cooperatives has its own emblem, a colored ribbon, that helps the workers at the plant to identify the loads and allows them to keep track of the clams that enter and leave the plant.

In the plant, the workers close the shells with rubber bands to protect them and prevent them from opening during transportation to market. They are placed in boxes lined with sponge and then packed into tanks of oxigenated water replenished by pipes. A maximum of two to three thousand clams are gathered in the tank over a four day period. They are fed shrimp larvae on the fourth day. Each box contains fifteen clams and each tank has a ninety box capacity.

Transport and Sale

On the road to obtaining their own commercial sustainable harvest permits, the cooperatives in Puerto Peñasco send their product by truck to Ensenada. Because the clams are shipped live, each truck has a watering system that keeps the clams moist. The maximum load per truck is 4,000 clams. A wet sack on top of each crate maintains the temperature between 68° F and 86° F and helps to keep the clams alive until they arrive at their destination.

Not all of the clams survive the trip so they are returned to the plant. These are consumed by the plant workers and their shells are used as filter material for the processing tanks or are discarded.

This process is carried out year round by the cooperatives and currently its economic impact brings benefits to about 43 families in the community. According to Rosa María Chaides Ibarra, head of Quality Control for the Mar y Tierra Cooperative, they hope for a greater return in the future because now they only receive between $2 and $8 for each clam, depending on its size, color and thickness.

*Members of CEDO and ITSPP (Advanced Technological Institute of Puerto Peñasco) respectively