Jaguar: Challenge for the Americas

Jaguar conservation expert and staunch defender, Dr. Alan Rabinovitz visited the mountains between Jalisco and Nayarit, one of the most important boreal areas for the mythical tecuani of the ancient Mexicas. Click on image to enlarge. (Photo: Courtesy of Viaje del Jaguar).

TEPIC

There could still be about 100,000 jaguars in all of the Americas, says Dr. Alan Rabinovitz, one of the world’s most renowned experts on big cat conservation. But he warns: “we can’t be complacent; a hundred years ago there was a similar number of tigers in southeast Asia, and in just a few generations they have almost disappeared. This mustn’t be the story of the jaguar.”

Rabinovitz is cofounder of Panthera, an NGO that proposes to work with governments to carry out ambitious conservation projects for big cats around the world. The organization’s premise is that predators are indicator species, and are responsible for sustaining ecosystems.

Panthera is just one genus in the family Felidae (according to Linnean nomenclature) and includes just a a few species of big cats, all of which are capable of roaring: lions (Panthera leo), tigers (P. tigris), leopards (P. pardus), snow leopards (P. uncial) and jaguars (P. onca).

But the organization’s mission goes beyond these charismatic beasts, recognizing as well that it is vital to protect Africa and Asia’s cheetahs, the world’s fastest terrestrial animal, and mountain lions (pumas), a dominant American feline that, according to scientists, is the big cat best adapted to a wide range of climates and ecosystems.

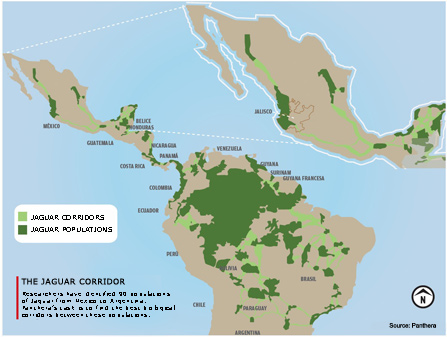

Rabinovitz is a legend. His name is connected to both Hukaung Valley Tiger Reserve in Myanmar (formerly Burma), the world’s largest natural reserve for the endangered Bengal tiger, and Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary and Jaguar Preserve in Belize, the first preserve dedicated to saving jaguars in the Americas. He has also proposed the idea of jaguar corridors, a concept that is now the backbone of all Mesoamerican efforts to protect the only Panthera in the New World.

According to the National Geographic documentary about Rabinowitz’ life, struggle has been the leitmotif: for big cats, and against a stutter, cancer, and the social hardships faced in his native New York. Time called him the “Indiana Jones” of wildlife protection.

In May 2017, he was in Mexico, where Rodrigo Núñez Pérez, president of the country’s Jaguar Conservation Committee, took him to visit the mountains between Jalisco and Nayarit, one of the most important boreal locations and ranges for the ancient Mexicas’ mythical tecuani.

Between meetings, he had time for a telephone conversation, and with the translation assistance of Diana Friedeberg, Panthera’s Mexican director, this is part of the conversation:

- What is Panthera hoping to accomplish with this visit to Mexico?

- We are starting a large-scale initiative called Journey of the Jaguar (Viaje del Jaguar) that entails traveling along the jaguar’s trajectory from Mexico to Argentina in order to assess the conditions of the corridors, highlight the importance of Panthera onca in these zones, and to witness the collaboration of other groups working on conservation of the species. We have realized that in Mexico there are many NGOs working on efforts, rescuing individual animals, as well as ejidatarios and land owners who want to use their land for conservation. Then there are governmental efforts. But these are all isolated efforts that need to be coordinated, so that together they will all help us achieve real jaguar conservation.

- We live in times with a lot of “green” political rhetoric, but public budgets not only are not increasing, but are actually being reduced and it doesn’t look like there are enough resources for long term conservation.

- Yes, this true and not only in Mexico; this is happening with the other 18 governments we work on jaguar conservation. Many make promises, but then always complain that there aren’t enough funds to follow through. We believe that there are the resources but that they just don’t prioritize conservation projects; they don’t place much importance on priority species like the jaguar. It seems that they see the importance of conserving green areas and beautiful landscapes, but they don’t see the rest as being necessary for our future, for human health and well-being. The reality is that natural protected areas have an essential function. We depend on them for their ecosystem services: water, air, and everything that we extract from the earth; and for climate change mitigation. All of this, both conservation and ecology has to be prioritized by governments.

- How did the health of the jaguar seem, given data from the monitoring projects and the species’ widespread distribution, especially when compared to the vulnerability of other worldwide Panthera species?

- Compared to other big cat species, the jaguar actually looks to be in good shape; its population numbers are good. On the other hand, the tiger and lion are close to extinction. I have to point out something though about the 100,000 jaguars that still remain in the world: 100 years ago, we had the same number of tigers and in that same amount of time we have lost most of their populations. This is what we want to avoid with the jaguar, because in three or four generations we could have just half that number.

- What threats to the species have you identified?

- Among the threats are poaching, of the jaguar itself and of its food prey. Another problem is that while there are numerous populations, they are isolated from each other. At least there are these biological corridors that we can use to connect the populations, because isolated populations lead to the extinction of a species. They need a strong genetic bank, and this can be achieved if corridors from Mexico all the way to Argentina are maintained (see map), and if the populations remain related to each other. That will mean we have jaguars into the future.

- Would a local economy that is sustained by the survival of jaguars be possible?

- Yes, definitely, using it as a charismatic species. Every Mexican has a jaguar in his or her heart, so it might be the ejidos that could work with them to develop some type of ecotourism, where adventure seekers would pay for a trip and could also learn all about the culture surrounding the jaguar. This culture isn’t just relevant to the biological and genetic corridors in Mexico: this is where the jaguar’s cultural path began. It is from the pre-Hispanic cultures in the region that the cosmic view of the jaguar arose, especially among the Olmecs, and all aspects of their lives revolved around this species. This is a precious legacy that could be drawn upon to promote conservation.