Sea turtles have traversed the world's oceans since before the dinosaurs roamed the earth. Five of the world's seven marine turtle species can be found off the coast of the Baja California peninsula. All are endangered. Learn about turtle biology and the people who are trying to save these magnificent living fossils.

You'll find links to the class handouts used at ISSI (Intensive Spanish Summer Institute) here and in the ISSI archives. You can also link to the vocabulary list for this topic or see the spanish translation by clicking on individual red words in the text below.

And be sure to check out our three short videos taken in Jan. 2014 at a turtle hatchery in BCS.

Sea Turtle Natural History

Like all turtles, sea turtles are cold-blooded, egg-laying, air-breathing reptiles. All but one species has a hard shell composed of scales or scutes. They belong to the order Testudines and present day species are divided into two families, Cheloniidae (six species) and Dermochelyidae (one species). Of the seven extant species, five are almost cosmopolitan in their range while the Flatback (Natator depressus) is limited to northern coastal waters of Australia and the Kemp’s Ridley (Lepidochelys kempii) is restricted to the Atlantic & Caribbean waters of the Americas.

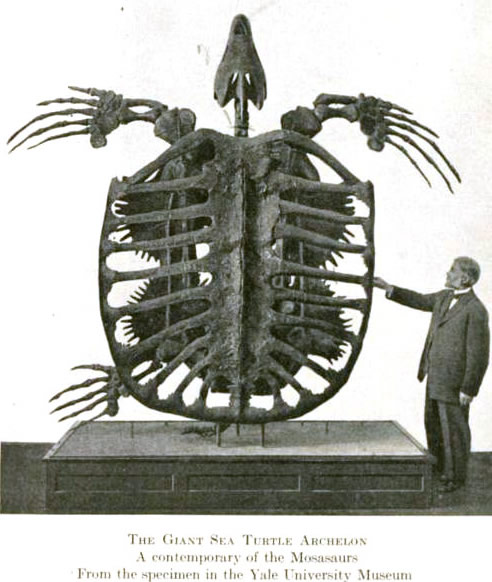

Sea turtles have lived on Earth for at least 200 million years. The most intact fossilized remains of the world’s largest sea turtle species, Archelon ischyros (pronounced Ar-key-lon is-key-ros), was found in South Dakota in the 1970’s and was dated at 74 million years old. The fossil measures 15 feet long from beak to tail, and 16.5 feet across from flipper to flipper. The live animal probably weighed about 4,500 pounds and the species may have lived to about one hundred years old. This, and other specimens discovered date from the Cretaceous Period (75-65 mya) when the Midwest region was covered by a shallow sea. The basic design of the smaller present day species has changed little from that of their ancient ancestors, though, like Archelon, they probably had a leathery carapace (shell).

Sea turtles, once they hatch and make their way to the ocean, will never set flipper on land again, except in the case of mature females who will come ashore every two to four years to dig from 4 to 7 nests per season. The number of eggs laid (70-180) and the incubation period (52-65 days) depends on the species and nest temperature. Nest temperature also plays a role in the determination of sex, with temperatures above 30º C (86ºF) producing females, while those below 28º C (82º F) will produce males. Nests must also have ample moisture and air for proper egg development and hatchling survival. Watch three short videos of hatchlings being released in Baja California Sur.

Olive Ridley hatchlings,

San Cristóbal, BCS

Young turtles (tortuguitas) spend many years in open ocean waters, floating within seaweed and debris rafts, evading predators while feeding and growing. Once they have reached an adequate size to be less of a tasty morsel for predators such as sea birds and larger fish, they will make their way towards the coast to feed, remaining either well offshore or venturing closer in to shallow waters. Most are opportunistic omnivores and will eat according to available food sources. Some species of sea turtles prefer crustaceans (crabs, shrimp), mollusks (snails), cephalopods (squid, octopus) or jelly fish. The Hawksbill finds sponges a delicacy while sea grass and algae is more to the Green’s liking.

Five species of sea turtle occur in high concentrations off of the Baja California peninsula in either the Pacific Ocean or the Gulf of California (see chart below). This concentration constitutes a large portion of the respective species’ regional population. This area is a major feeding ground for all five species as well as a minor nesting area for three (Green, Olive Ridley and Leatherback). Turtles feeding in the Baja California region will spend most of their lives there except for when they migrate elsewhere to breed. The principal nesting area for the Olive Ridley population is the west coast of mainland Mexico from the state of Sinaloa south to Costa Rica. Once they reach maturity, they will migrate between June and November to the nesting grounds where they will mate and the females will go ashore to nest. Ridleys participate in mass nesting events called arribadas (literally "landing" or "the arrival”).

Common Name (US) |

Nombre Común (México) |

Scientific Name |

| Green/Black | Tortuga prieta, Tortuga negra | |

| Hawksbill | Carey | Eretmochelys imbricata |

| Leatherback | Tortuga laúd | Dermochelys coriacea |

| Loggerhead | Tortuga amarilla, Tortuga cabezón | Caretta caretta |

| Olive Ridley | Tortuga golfina | Lepidochelys olivacea |

In the early 1990’s, a connection between Loggerhead turtles off the Pacific coast of the peninsula and those in the waters of Japan and the South China Sea was scientifically established. After an ID tag from a dead Loggerhead that had been marked off Baja California was recovered by a fisherman in Japan, scientists set out to confirm a long-held theory of a connection. In 1996 researcher Wallace J. Nichols was the first to successfully track a mature female Loggerhead named Adelita using a satellite transmitter attached to her shell as she traveled almost directly from Baja to Japan. Since then, several other mature female turtles have been tracked and this data, along with DNA evidence, has proven that Loggerheads born on the beaches of Japan (as well as other Asian countries) migrate about 5,600 miles across the Pacific to spend their adolescence along the Baja California peninsula and then as adults return to remain in their natal waters where they will mate and nest. For more information, visit The Remarkable Journey of Adelita, the Loggerhead Sea Turtle.

To find out more about sea turtles, visit our bilingual Turtle Fact Sheet. Visit the National Oceanic Society page where you can for 11 Amazing Sea Turtle Facts (and find lots more resources) or check out Sea Turtles: The Ultimate Expert Guide.

Turtles and Human Interaction

Sea turtles have historically been an important source of protein in coastal populations world wide. Many indigenous cultures have revered sea turtles and include them in their religious ceremonies. Sea turtles continue to play a central role in the culture of the Comca' ac Nation (the Seri) of Sonora, Mexico and the tribe has become an active participant in the sea turtle conservation movement. A traditional Turtle Island story of the Onondaga tribe (New York state) tells of the Earth being supported on Turtle’s back. In Baja California, sea turtle images possibly as old as 7500 years are depicted as rock paintings found on cliffs and cave walls in remote canyons throughout the southern peninsula, indicating that these peoples were familiar with the animals and that turtles must have held some significance within their culture to have been depicted in their art. Mexicans have long believed that turtle meat and blood have medicinal properties and that the eggs have aphrodisiacal effects. These traditions and myths persist to this day in many areas and present a great obstacle to sea turtle conservation.

Endangered Species

Currently all seven species are recognized by the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature, 2016) as either vulnerable (Olive Ridley & Leatherback), threatened (Loggerhead), endangered ( Green & Flatback), or critically endangered (Hawksbill & Kemp’s Ridley). They are protected worldwide by the Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Between 1975 and 1981 all species were added to the CITES Appendix 1, a list of the world’s most endangered species. International trade of these species is strictly prohibited by the treaty. Mexico’s sea turtles are specifically protected within Mexico by federal decree (NOM-059-ECOL-2001) and the Carta Nacional Pesquera of 2004, although enforcement continues to be problematic. In spite of all these protections, illegal, unsustainable consumption continues in Mexico as well as worldwide. In northwest Mexico and the southwest United States alone, at least 30,000 turtles are slaughtered and sold on the black market annually mostly during Easter, Christmas and other important religious holidays, where the eating of turtle meat is not considered to break the dietary rule of abstaining from eating meat on certain days. National holidays as well as political and social events are also times of increased turtle consumption and even officials working on environmental issues have been known to procure a turtle meal for their honored guests.

Poaching for personal or commercial consumption is not the only factor contributing to the sea turtles’ plight. Incidental by-catch is another major cause of turtle mortality, killing untold thousands yearly. They drown after they are scooped up in trawl nets lacking turtle exclusion devices (TEDs) or snagged in gill nets or on long lines designed to catch large fish such as swordfish or tuna. They are injured by boat propellers or drowned when they become entangled in old nets and fishing lines (ghost nets). Chemical contaminants (such as PCBs–polychlorinated biphenyls–or the heavy metals cadmium and lead) weaken individuals and may affect long term fertility. They choke on plastic bags (commonly mistaken for jellyfish). Even the eggs are not safe once they are laid. Poachers can easily decimate a season’s crop on an entire beach in some areas, as can wild and feral predators (coyotes, raccoons, wild pigs, feral dogs) that raid or otherwise disturb the carefully constructed nests.

Last but not least, the loss of pristine nesting habitat is reducing the rate of repopulation of the species as beaches are consumed for tourism or industrial projects. Coastal development brings with it invasive dune plant species that make nest digging difficult. Off-road vehicles run rampant, compacting the sand and suffocating eggs. Nocturnal lighting from hotels, homes and streets can confuse the hatchlings’ ability to navigate safely and quickly toward the ocean. And it can be only assumed that global climate change will further contribute to this loss of habitat if, as projected, a substantial sea rise occurs.

Unchecked human exploitation of sea turtles, the continued systemic denial of the connection between human activity, environmental contamination and degradation, and our patent disregard for the health of the environment and all of its unique ecosystems have placed the sea turtle, among many other species, in a tightening, downward spiral. However, there are a growing number of individuals worldwide who have taken up the call to explore and address these issues as they pertain to sea turtles and in doing so, perhaps these efforts will have some rippling effect in the collective consciousness.

Conservation Programs—Grupo Tortuguero de las Californias (GTC)

In 1999, a small group of international scientists, community activists and local fishermen came together in Loreto, BCS for the first time to form The Sea Turtle Conservation Network of the Californias, now officially known as Grupo Tortuguero de las Californias. Their goal was to better understand and address the factors that were leading to the decline in the Eastern Pacific sea turtle populations. A drastic decline had been witnessed in nesting populations worldwide during the 1970’s and 1980’s. By the mid 1990’s marine scientists and environmental groups were becoming ever more alarmed by the continued decline.

In Michoacán, on one beach alone, the number of nesting females coming ashore during a weekend-long arribada was seen to decline from 25,000 in 1970 to less than 500 in 1999 (just 2% of the previous population). The meeting launched Grupo Tortuguero’s conservation work which started with a few fishing villages where there was a history of heavy poaching as well as an expressed interest in the project by local people. In the intervening years, the group has brought together fishermen, poachers (now ex-), government officials, scientists, school children, business people and environmental activists to work both within individual communities and on a regionally coordinated basis. The group uses a number of different approaches and works to promote behaviors and social norms that will help to preserve turtles and their environment.

In Michoacán, on one beach alone, the number of nesting females coming ashore during a weekend-long arribada was seen to decline from 25,000 in 1970 to less than 500 in 1999 (just 2% of the previous population). The meeting launched Grupo Tortuguero’s conservation work which started with a few fishing villages where there was a history of heavy poaching as well as an expressed interest in the project by local people. In the intervening years, the group has brought together fishermen, poachers (now ex-), government officials, scientists, school children, business people and environmental activists to work both within individual communities and on a regionally coordinated basis. The group uses a number of different approaches and works to promote behaviors and social norms that will help to preserve turtles and their environment.

Community-directed resource conservation continues to be central to GTC, whose leaders are chosen biannually from local community members. Members have benefitted through their work and involvement in GTC and new and dynamic activists have emerged from the least expected places. Perhaps Grupo Tortuguero’s greatest accomplishment has been the interconnectedness of communities and organizations that it has fostered both on a local and international level.

Environmental Education. This is a key component of GTC’s work, which uses the sea turtle as a flagship species, linking its success to the health of both marine and terrestrial environments as well as to the economic success of the region. Its national and international media campaigns have been innovative and many have addressed the myths surrounding turtles in Mexican society. Its workshops, scientific meetings and environmental festivals have helped to increase participant knowledge about the environment, current environmental challenges, and how individuals and communities can take proactive measures in its stewardship.

Information gathered from outside activities will be taken back to a participant’s community and may be incorporated there into further activities and workshops, assuring that information is cycled through the region. Many of these activities are geared toward children and youth, who are seen as future stewards of the area’s resources. “El futuro está en tus manos” is the motto of one local non-profit youth group.

Monitoring Program. Since 2001, GTC has managed a scientifically based monitoring program that is currently active in 40 locations in four Mexican states. The monitoring program brings much needed funding to local fisherman, and involves them as active participants in the research and protection of their local resources. Teams conduct a monthly monitoring where, over a 24 hour period, they capture, weigh, photograph, tag and release turtles. They receive a monthly stipend that covers expenses as well as a small salary. A number of the sites included in this project are involved only with the protection of nesting beaches and egg relocation to nearby hatcheries that they maintain and guard. Team members from each community are expected to attend and present their data at the annual monitoring meeting which is held in a different community each August.

In January 2008, its annual meeting was held in Loreto, BCS concurrently with RETOMALA (a network of Latino turtle conservationists) and the 25th Annual Symposium of the International Sea Turtle Society with over 1200 tortugueros in attendance.

At that meeting, a very positive action was discussed that marks the success of GTC's conservation program. As a result of his experience with GTC fishermen and scientists from Mexico, the US and Japan, the captain of a major Mexican fishing fleet working off the peninsula’s Pacific coast made a landmark decision. He voluntarily retired the fleet’s long lines, thereby making a commitment to the protection of at least 700 Loggerheads yearly that would have been killed by his fleet alone within a key turtle feeding hotspot. It is further hoped that local groups will be able to pressure the Mexican government to declare their area a national marine refuge, off limits to further large-scale commercial fishing harmful to turtles.

Grupo Tortuguero celebrated its 13th annual meeting in La Paz, BCS in January 2011 (read a short article in Spanish). At this meeting, scientific papers and monitoring project results were presented. In Puerto López Mateos, for example, it was reported that there was a 60% decrease in the annual number of beached turtles that had been killed in nets. There had also been an increase in the degree of local involvement with nine fishing Co-Ops and a total of 15 organizations involved. Other projects, in Loreto Bay and Laguna San Ignacio, have studied the distribution of turtle populations in those places to determine patterns of use by both humans and turtles. The goal is decrease the impact and mortality of turtles in those areas and help determine if further delimitation of protected or closed areas is warranted. In another community, Punta Abreojos, researchers want to look at the effects of heavy metals on sea turtles, a possible explanation for the apparently stunted size of specimens captured there.

Grupo Tortuguero celebrated its 13th annual meeting in La Paz, BCS in January 2011 (read a short article in Spanish). At this meeting, scientific papers and monitoring project results were presented. In Puerto López Mateos, for example, it was reported that there was a 60% decrease in the annual number of beached turtles that had been killed in nets. There had also been an increase in the degree of local involvement with nine fishing Co-Ops and a total of 15 organizations involved. Other projects, in Loreto Bay and Laguna San Ignacio, have studied the distribution of turtle populations in those places to determine patterns of use by both humans and turtles. The goal is decrease the impact and mortality of turtles in those areas and help determine if further delimitation of protected or closed areas is warranted. In another community, Punta Abreojos, researchers want to look at the effects of heavy metals on sea turtles, a possible explanation for the apparently stunted size of specimens captured there.

The 14th, and the 16th through 19th annual meetings were held in Mazatlán and hosted by the Acuario Mazatlán. Having gone through a few rough years financially and a reorganization, in January 2018 GTC hosted almost 200 attendees at their 20th anniversary meeting in Loreto, BCS. New acquaintances were made and old friendships rekindled. A variety of research reports were presented as were the yearly results from the monitoring and hatchery projects. In terms of the nesting beaches, there was an increase in the number of hatchlings released during the past season as compared to the previous year. There has been a stable yearly increase in the number of hatchlings released over GTC’s 20 years of conservation and the number of nesting females s at Colula and two adjacent beaches in Michoacán had returned this year to pre-1975 numbers.

Yearly meetings continue to be a focal point for sharing information and forming and/or strengthening inter-community and international alliances. From the original 45 people who formed GTC in 1999, the yearly meeting has grown. In 2013 attendance at the 15th Annual Meeting in Loreto topped 350. Today GTC is working with 50 communities across the two states of the Baja California peninsula and five other Mexican states as well as collaborating with groups in seven countries.

¡Viva la Tortuga! ¡Viva la Revolución Tortuguera!

Visit this page where you can watch short video interviews we took at GTC 13 in La Paz. Bilingual scripts are provided as you watch. See the real people involved in turtle conservation talking about their work and passion.

File Downloads

Bajar Documentos

- Sea Turtles Class Handout (ISSI)

- Sea turtles Presentation (ISSI)

- Presentación de las tortugas marinas (ISSI)

- Vocabulary list (ISSI)

Links

Enlaces

Euroturtle.org

Grupo Tortuguero (some bilingual pages)

International Sea Turtle Society

National Geographic Sea Turtle Gallery

Turtle Island Restoration Network

Wildcoast

SEE Turtles (conservation research/tourism)

Billion Baby Turtles (learn about and help fund conservation)

Saving Sea Turtles from the Ground Up: Awakening Sea Turtle Conservation in Northwestern Mexico

Conservación de la tortuga verde (Chelonia mydas) en México (article PDF 161kb)

Heroes del Mar (video excelente de 8 minutos, 2021)

Voluntarios Red de Protección a la Tortuga (video excelente de 7 minutos, 2020)

Mujeres que mueven Mexico (2022)

Illuminating the Mystery of Sea Turtles’ Epic Migrations (2017 article with new information about Loggerhead migration).

Tortuga Rising - short bilingual article from Orion Magazine (2013).

The Science Exchange at San Diego State University sets up internships in Baja California to work on sea turtle conservation.

More links to articles and videos can be found in the ISSI archive