BEE FEB 2015

The Good, The Bad, and The Prickly: Botanical Adventures in Baja California — Part 1

This month I was invited to give a talk in Loreto about Baja California plants. Over the next few installments, I´ll share my notes from that lecture, starting with an introduction to the flora and two of the peninsula´s phytogeographic regions.

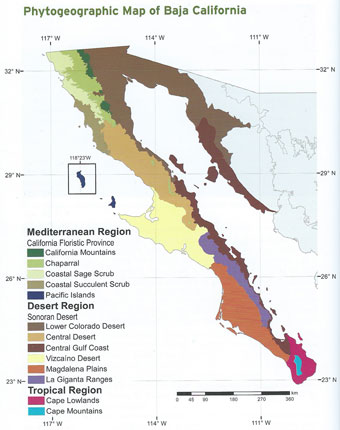

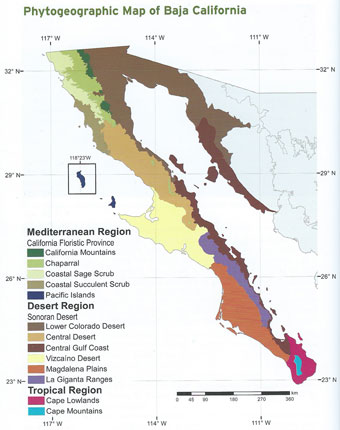

Baja California is divided into three principal phytogeographic regions, with each of these being further divided into subregions. In the northwest is the Mediterranean Region, which is a southward continuation into northwestern Baja California of what is known as the California Floristic Province. It is characterized by hot, dry summers and wet, mild to cold winters.

Baja California is divided into three principal phytogeographic regions, with each of these being further divided into subregions. In the northwest is the Mediterranean Region, which is a southward continuation into northwestern Baja California of what is known as the California Floristic Province. It is characterized by hot, dry summers and wet, mild to cold winters.

The majority (about two-thirds) of the peninsula falls within the Sonoran Desert Region, which is further divided into five subregions. The Desert Region is characterized by low rainfall (commonly lacking for years at a time), high summer daytime temperatures, and a high rate of surface evaporation.

At the far southern end of the peninsula, just north and south of the Tropic of Cancer, the vegetation belongs to the arid, Tropical Region, most commonly known as the Cape Region. This area is characterized by periods of drought interspersed with monsoonal weather patterns, and high summer temperatures and humidity.

There are over 4000 recognized species, subspecies and varieties of plants on the peninsula, and new finds are occurring more regularly as expeditions are mounted, primarily after summer tropical storms and hurricanes. In the past few years, the San Diego Natural History Museum has sponsored a number of trips by botanists, ecologists, entomologists, ornithologists and zoologists from both their and other institutions to under-explored areas of the Cape. They've made some interesting finds: species new to science, range extensions of previously known species and re-discovered species.

Somewhere between 23 and 30 percent of the peninsula's plants are thought to be endemic with the bulk of the remaining plants being native. According to Rebman & Roberts (The Baja California Plant Field Guide, 3rd Edition, 2012), there is no definitive source of information on exotic plants (introduced and/or invasive) with each research project yielding differing results. However, their own review of herbaria specimens suggests that there are over 240 species (<1%) of exotics capable of reproducing and surviving on the peninsula.

The Central Gulf Coast Subregion

I spend most of my time in and around Mulegé which is located within the Central Gulf Coast phytogeographic subregion of the Sonoran Desert. This is a hot, arid strip that extends along the eastern flank of the peninsula from the southern end of Bahía de los Ángeles south to the Bay of La Paz.

I spend most of my time in and around Mulegé which is located within the Central Gulf Coast phytogeographic subregion of the Sonoran Desert. This is a hot, arid strip that extends along the eastern flank of the peninsula from the southern end of Bahía de los Ángeles south to the Bay of La Paz.

The landscape varies across this narrow strip that is sandwiched between the Gulf of California on the east and a series of Peninsular Ranges on the west that make up the backbone of the peninsula. Moving from sea to mountain, rocky coast bluffs and cliffs, dunes and/or salt flats give way to alluvial fans braided by intermittent water courses (vados and arroyos) before ending abruptly at the steep eastern escarpment of the sierras.

Probably one of the most fascinating aspects of this region is the abrupt interface of desert and sea. Here, desert vegetation on rocky cliffs extends right to the Gulf.

A well-vegetated coastal dune. Some dunes are merely bumps of sand that give way abruptly to desert vegetation, while others, like these, have a discernible beach strand, foredunes and rear dunes that blend into the desert scrub.

The vegetation is commonly denser on the alluvial fans, which have deeper soils and retain more moisture than the rocky, thin-soiled hills. Cardon cacti dominate this scene, accompanied by Cholla, Ashy Limberbush and Galloping Cactus (Stenocereus gummosus).

An extensive salt flat bordered by sand dunes. The hillside from which the image was taken is an ancient marine bed that has been exposed with changes in sea levels or coastal uplift.

Typical sparsely vegetated rocky hillsides, with the dominant foreground shrubs being Limberbush, Creosote and Chain-link Cholla (Jatropha cuneata, Larrea tridentata and Cylindropuntia cholla).

The abrupt transition from flats and bajadas (alluvial fans) to the sierras is similar to that demonstrated in this image of a wide, sandy arroyo bound by steep hills and cliffs. The soils are primarily of volcanic origin and vary from solid rock to loose talus slopes.

In spite of the aridity of the Central Gulf Coast subregion, it is rich in species diversity. To date, in and around just the Mulegé area and the foothills of the Sierras to the west, I have documented nearly 400 species of angiosperms, one fern, one gymnosperm, two liverworts and eight mosses. I am sure that there are still many species to be collected, given the right conditions and blind luck while exploring.

Xerophytic, sarcocaulescent scrub is the primary vegetational pattern in which the dominant species have thick, water-storing trunks and stems. More specifically, these species include Bursera spp., Jatropha spp., and cacti like the Cardón (Pachycereus pringlei) and Chollas (Cylindropuntia spp.). More entries about this region's flora can be found on these pages:

Post-Hurricane Paul (2012-13) plant season notes - Dec, Jan, Feb, Mar, Apr, May, June.

2014 entries: Jan & Feb & Mar & May.

Elephant Tree (Bursera hindsiana), known locally as Torote Prieto or Copalquín, is a member of the Torchwood Family, as are Frankincense & Myrrh.

B. hindsiana bark is smooth and solid gray, but sometimes has red undertones, as above. The leaves are broad, single, 3- or 5-foliate, fuzzy and drought-decidous. As the drupes dry, the bright red and black seed is exposed, attracting birds. They are usually gone by November. Both species exude a clear, aromatic resin.

The tiny flowers (c. 2.5 mm L) of B. hindsiana usually bloom in the summer when the tree is leafless. The flowers are fuzzy and bell-shaped.

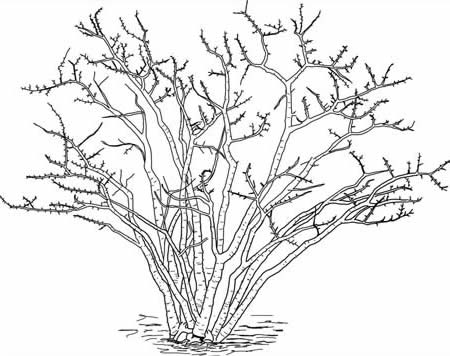

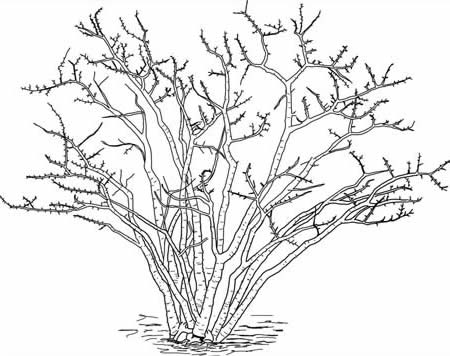

Ashy Limberbush or Lomboi (Jatropha cinerea, Euphorbiaceae) is a medium to large shrub that spends much of its life leafless. Its bark is silvery gray and smooth. The stems are often wand-like with large (2-4+ cm L) sparsely distributed, lateral spurs.

The large (4-8 cm L x W), distinctive heart-shaped leaves of J. cinerea grow rapidly & disappear just as fast once moisture from summer rain has dried up.

The large (4-8 cm L x W), distinctive heart-shaped leaves of J. cinerea grow rapidly & disappear just as fast once moisture from summer rain has dried up.

The leaves and flowers of J. cinerea. Both species have urn-shaped flowers. This species has large clusters of flowers.

Dipúa or Littleleaf Palo Verde (Parkinsonia microphylla, Fabaceae) is another of the dominant trees in the region. It lacks spines.

The white banner petal of Dipúa turns yellow like the rest of the petals once the flower is fertilized, perhaps a signal to pollinators.

Little-leaf Elephant Tree (Bursera microphylla), known locally as Torote Colorado. This tree usually has branches more contorted than those of B. hindsiana. Both can be several meters in height.

B. microphylla bark varies from pale yellow to a orange and peels, as can be seen above. The leaves are tiny and pinnate and while drought-decidous, can last months beyond those of its cousin on the left. The drupes are fleshy and an important food source for birds and rodents through the winter and spring.

Flowers of B. microphylla are c. 4 mm L and bloom in the summer when the trees are mostly leafless. The petals are spreading to reflexed.

Limberbush or Matacora (Jatropha cuneata) is a small to medium shrub that also spends much of its life bare. The bark is rough with horizontal lines, and ranges from yellow, green, brown to blackish. It's short, knobby lateral spurs are distinctive.

Ample late summer rain transforms Matacora (J. cuneata) from just another gray, "dead" bunch of sticks to a healthy, dense bush whose leaves may last through the winter and well into spring. The small (1-2 cm L) leathery leaves are much more drought tolerant than the large, thin leaves of Lomboi (J. cinerea).

The leaves and flowers of J. cuneata. Flowers of Jatropha spp. are monoecious or dioecious and often dimorphic.

When water is scarce, Dipúa loses its tiny (1-2 mm) water-conserving leaflets and carries on with photosynthesis within its green bark.

The legumes of the Dipúa are distinctive amongst all the Fabaceae on the peninsula, making the species easy to identify. Read more here.

The Sierra de la Giganta Subregion

Mulegé is flanked on the west above 200 meters elevation by the Sierra de La Giganta phytogeographic subregion. Traveling inland from town and upon leaving the flat valley bottom, one soon enters this subregion as the road climbs sharply up through a couple of canyons and along a few hillsides into the heart of the mountains (Sierra de Guadalupe in this area). This is also true northward as far as San Ignacio and southward past Loreto and into the Comondus.

Mulegé is flanked on the west above 200 meters elevation by the Sierra de La Giganta phytogeographic subregion. Traveling inland from town and upon leaving the flat valley bottom, one soon enters this subregion as the road climbs sharply up through a couple of canyons and along a few hillsides into the heart of the mountains (Sierra de Guadalupe in this area). This is also true northward as far as San Ignacio and southward past Loreto and into the Comondus.

The most noticeable change in the vegetation is the increase in larger shrubs and small trees that tend, at least in the winter and spring, to be much leafier than below in the lowlands. Many of the same species continue up into this region, but the dominant plants are considered to be leguminous trees such as Lysiloma candidum, Parkinsonia microphyllum and P. praecox, and the endemic Palmer’s Mesquite (Prosopis palmeri).

Read previous entries from field trips to these areas:

San José de Magdalena, San Patricio, & La Sierra de Guadalupe.

View back down the canyon traversed by the highway into the Sierra de la Giganta west of Loreto.

Palo brea (Parkinsonia praecox subsp. praecox) is a small, native tree with bright green bark that extends from ground level up. It is one of four species on the peninsula.

Higuera Cimarron or Zalate. This native fig (Ficus petiolaris) grows to spectacular heights and shapes, melding onto cliff faces and boulders.

Higuera Cimarron or Zalate. This native fig (Ficus petiolaris) grows to spectacular heights and shapes, melding onto cliff faces and boulders.

Huizache or Vinorama (Acacia brandegeana, Fabaceae) is an endemic large shrub or tree common to the region.

Bird's-foot Morning Glory (Ipomoea ternifolia, Convolvulaceae). After rain, this region is often abundantly carpeted in vines and other annuals that are more common here than in the Central Gulf Coast Region.

Bird's-foot Morning Glory (Ipomoea ternifolia, Convolvulaceae). After rain, this region is often abundantly carpeted in vines and other annuals that are more common here than in the Central Gulf Coast Region.

A natural cactus garden. The desert scrub is often more dense and has a higher species diversity.

Flowers and fruit of Palo Brea. It has small stipular spines. It is more common in the Sierra de la Giganta and southward, extending all the way to the Cape. It occurs elsewhere in the Americas.

The Palo Blanco's unique white trunks make this species (Lysiloma candidum, Fabaceae) easily recognizable on cliffs, hillsides and arroyo bottoms.

The Palo Blanco's unique white trunks make this species (Lysiloma candidum, Fabaceae) easily recognizable on cliffs, hillsides and arroyo bottoms.

Palo chino or Teso (Acacia peninsularis, Fabaceae) is also an endemic large shrub or tree in this region.

Another beautiful and bountiful vine is the endemic Yuca (Merremia aurea, Convolvulaceae) which occurs from around Loreto and southward. The fruit is a papery capsule, pictured here (uppermost) inside the large, spreading sepals.

Another beautiful and bountiful vine is the endemic Yuca (Merremia aurea, Convolvulaceae) which occurs from around Loreto and southward. The fruit is a papery capsule, pictured here (uppermost) inside the large, spreading sepals.

A second noticeable difference in the Sierra de la Giganta subregion is the presence of above ground water sources, such as small streams, rocky watering holes (tinajas) and seeps. The fractured, volcanic nature of the underlying rocky substrate has led to subterranean water sources and aquifers that issue forth after rains or are even present throughout most of the year.

A second noticeable difference in the Sierra de la Giganta subregion is the presence of above ground water sources, such as small streams, rocky watering holes (tinajas) and seeps. The fractured, volcanic nature of the underlying rocky substrate has led to subterranean water sources and aquifers that issue forth after rains or are even present throughout most of the year.

The presence of these permanent water sources was important to the prehispanic, indigenous hunter-gatherer tribes on the peninsula and then later to the missionaries who were able to traverse the length of the peninsula and establish their missions along the way alongside many of these permanent oases. In modern times, they support not only the native animals but small goat and cattle ranches, often with date palm and fig orchards as well as vegetable gardens.

Deep, shady canyons with palms are common in this subregion. Aquatic species are few, with reed-like species most prevalent.

Semi-permanent ponds in slick rock (tepetate) are also common in the region's canyons.

Rain in these mountains brings life to the desert vegetation and animals that depend on it. But it also can lead to destruction as the runoff from the steep hillsides with their hard-packed, impermeable soil and rocks is directed downhill and into gullies and arroyos, eventually causing devastating flashfloods downstream (for more, see last month´s entry).

Until next month's installment when I'll talk about "the Good", hasta la próxima…

Debra Valov—Curatorial volunteer

Map source: Rebman, Jon. P. and Roberts, Norman. (2012). The Baja California Plant Field Guide, 3rd Ed. Sunbelt Press.